New York Amsterdam News building that was home to the paper from 1916–1938.

Photo: Library of Congress

Amsterdam News: Born in San Juan Hill, Raised in Harlem

Amsterdam News: Born in San Juan Hill, Raised in Harlem

July 11, 2023

by Ron Scott, Music Writer with the Amsterdam News

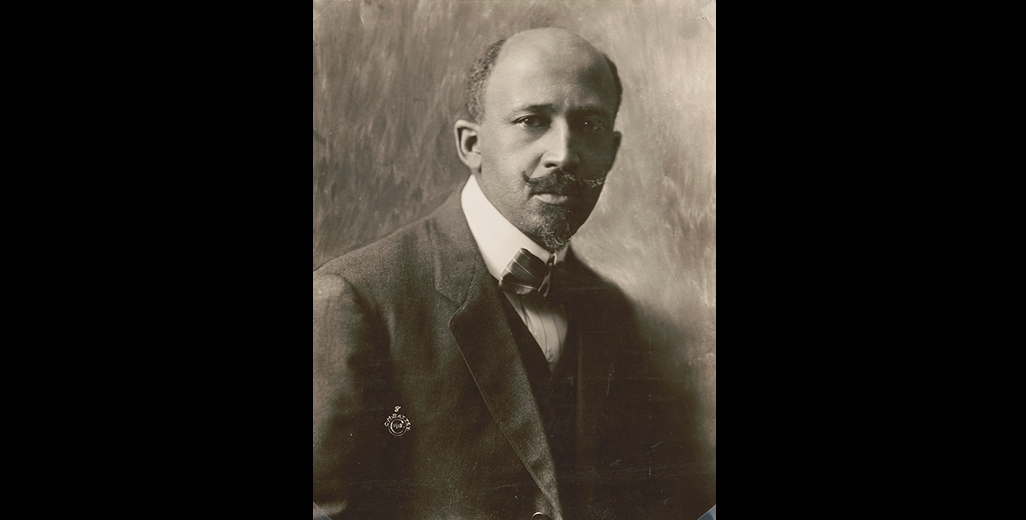

Decades before the wrecking ball was slated to crumble the thriving community of San Juan Hill, the Amsterdam News took its first breath on December 4, 1909, born in the apartment of its founder James H. Anderson at 132 West 65th Street. It was the same year another San Juan Hill resident, W.E.B. Du Bois, co-founded the NAACP.

Every morning upon awakening, Anderson was inspired by his picturesque view of Amsterdam Avenue, the neighborhood’s main hustle-bustle thoroughfare. For him, that avenue absolutely reflected his new publication. With six sheets of blank paper, a lead pencil, a 5’ x 4’ dress-makers table, and his hard-earned $10, Anderson—without any previous experience—ventured into the world of journalism.

According to a notebook found in Anderson’s belongings, he wrote, “I was a traveler, born in Columbia, S.C. on December 15, 1867. I ran away from home at about 12 years old, to my uncle’s house, James Henry Anderson and his wife, Tanner. He adopted me and renamed me after him…and I dropped my family name of Goode.” His travels took him to Wilmington, NC, Jacksonville, FL, Newport News, VA, and finally, to Brooklyn NY in 1883. There he worked as a bellhop, baker, and sexton, and he briefly owned a sign poster business, but he had dreams of becoming an editor and publisher. Why Anderson pursued a career in journalism is rather vague. However, we can surmise from his consistent, detailed notebook that he was an avid writer, a businessman, and a negotiator, having held such varied positions during his travels.

The Amsterdam News debuted just 44 years after the signing of the 13th Amendment, abolishing slavery. The United States was shamelessly in the midst of Jim Crow lawlessness and lynchings. Anderson and Black newspapermen throughout the United States were committed to reporting these atrocities of social injustice, along with the positive aspects of Black life.

The Amsterdam News’ maiden voyage edition was published on December 4, 1909, was six pages long, and sold for one cent (today’s equivalent of $1). Its front page contained four columns of display advertisements, a two-column picture and biographical sketch of Anderson, a half-column of “city briefs,” a quarter-column of YMCA events, two columns of “Afro American Cullings” (editorials from other newspapers concerning the negro), and a full-column editorial calling for people to support the new paper. The first edition was extremely small compared to the 24 pages it boasted just eight years later, at which time the Amsterdam News was becoming one of the most influential and oft-cited Black, weekly newspapers in the country. (By 1927, the paper, with an expanded staff of journalists, had amplified its voice of truth against power. For example, its reporting uncovered the Sears-Roebuck Company’s discrimination against negroes buying houses. It was also waging an unrelenting battle against police brutality in San Juan Hill and Harlem through its coverage. On more than a few occasions, the Amsterdam News managed to get big scoops ahead of the major daily publications.)

As numerous Black newspapers were flourishing in the United States, Anderson focused on his main two New York City competitors; New York Age (co-founded by former slave T. Thomas Fortune in 1887) and the Chicago Defender (making its first inroads into the city under publisher Robert S. Abbott). Both focused on national affairs, such as Jim Crow laws and racial injustice, although the local New York Age provided some area news. Anderson saw an opening, a niche to concentrate on San Juan Hill, local events, its residents, and metro city items. Anderson made sure his readers knew it was strictly a local paper by printing on the front page, “Paper specializing on New York City news and resolved to seize it.”

San Juan Hill was a breeding ground for what Harlem would eventually become with its culmination of culture and night life, heavily populated by African Americans and people of color. Anderson was actively involved in community affairs as a member of such fraternal organizations as the Masons, Grand United Order of Odd Fellows, and the Elks (who sold his paper at their social events and meetings), as well as the Emancipation Commission of New York. The Amsterdam News was the visible voice of the overlooked Black community; it covered racial tensions between Blacks and Irish communities, police brutality, working-class struggles, Black society, and local weddings. San Juan Hill’s nightlife, with its dance halls and swinging jazz and Latin basement clubs, was listed under local happenings. During those early issues, in addition to being the publisher, Anderson was also the editor—and he did all the writing. However, as a member of many prominent organizations, it is very possible that some of his fraternal brothers assisted him in crafting articles. Anderson had wanted the Amsterdam News to be a daily, but soon realized it was enough work trying to get it out weekly.

During the paper’s first five months of operation, Anderson was a sole proprietor serving as financier, reporter, editor, advertising manager, distributor, and promotions manager. His most laborious task was hand-delivering papers to newsstands. To stimulate sales, Anderson devised a street promotion strategy. He organized a team of young boys, and he paid them a nickel each to stop at neighborhood newsstands and purchase four papers while declaring, “I need to buy that outstanding newspaper, the Amsterdam News.” They would then give out the purchased papers on the street, and their payment was that last penny. Anderson also purchased newspapers that he nonchalantly offered passers-by in his San Juan Hill neighborhood. This was an easy task, living among blossoming small businesses with a persevering working-class of Black porters, tailors, drivers, dock workers, and shopkeepers. And though it’s not documented, he may have given papers to, or befriended, a few of his more famous neighbors like composer/bandleader James Reese Europe and Arturo Alfonso Schomburg. As another promotional tactic, while on a trolley ride, he would select a seat next to a Black person while prominently displaying the Amsterdam News. After a few stops he would get off, strategically leaving the paper behind.

Still looking to entice readers with more pizzazz, Anderson introduced his “rubberneck column,” featuring community gossip and criticism, but no scandals. For instance, the rubberneck reporter would write, “Mr. J should be more careful about carrying a certain young lady’s groceries home so often, your wife maybe looking out the window.” The new column raised eyebrows and circulation. Anderson also added a reprinting of the famous short story “The Siege of Berlin” by French novelist Alphonse Daudet and a poem by Frenchman Richard Le Gallienne. He was the first among Black New York editors to introduce fiction in a newspaper. Next, he included a weekly sermon by his friend, Reverend Richard M. Bolden, then the pastor of Mother AME Zion Church located at 127 West 89th Street, who allowed the sale of the paper at his church on Sunday.

Anderson’s relationship with the church extended the Amsterdam News’s circulation uptown beyond the San Juan Hill community and going downtown to the Tenderloin district, known today as Midtown, where another Black working- and middle-class community flourished. This neighborhood boasted one defining jewel, the Marshall Hotel at 127-29 West 53rd Street, the only Black-owned, elite hotel in New York City, a property of businessman Jimmy Marshall.

It would be some years before Harlem’s Hotel Theresa dismissed its “White Only” policy instituted upon its 1913 opening. In the interim, from 1900 to 1913, the Marshall Hotel was the place where people of different races (Black and white) could meet and “socialize on equal ground.” It was a nucleus for artistic and intellectual expressions of Black culture where the formative concept of the NAACP was discussed.

The interaction at the Marshall was a change in Negro artistic life, it was a perception of the “New negro,” as stated in James Weldon Johnson’s book Black Manhattan (1930). Patrons who frequented the hotel included: W.E.B. Dubois, James Reese Europe, Paul Lawrence Dunbar, Aida Overton, Florenz Ziegfeld Jr., and Harold “Stretch” Johnson, the nephew of the Amsterdam News founder Anderson. Johnson modeled himself after his uncle, an activist who denounced lynching and characterized African-Americans as a developing nation prior to Marcus Garvey’s movement and the Nation of Islam.

After only one year, the paper’s increased circulation gave Anderson access to a multiplicity of Black communities in Manhattan, who acknowledged the Amsterdam News as “the people’s paper.” It was 1910, the beginning of the “Great Migration,” and as Black people departed from the rural South to big, northern industrial cities like Chicago, Philadelphia, and New York, many made their way to the village of Harlem. This was where Anderson wanted to be! He packed up, leaving San Juan Hill behind and moved the Amsterdam News uptown to 17 West 135th Street, raising the paper’s price to 2 cents. Sales increased enormously upon his move to Harlem, but Anderson felt he needed a partner for the paper’s continued escalation.

So, he teamed up with Edward A. Warren, a photographer and promoter, who also financed the paper during its indigent times. He invigorated the advertising department and became the paper’s treasurer, and later, its publisher—with Anderson moving to editor. Warren catapulted the Amsterdam News to be Harlem’s top newspaper. Outgrowing their office in 1916 with a staff that had grown to 14, they moved down the street to 2293 Seventh Avenue. After the death of Warren in 1921, his widow Sadie eventually married William H. Davis. After the couple purchased the paper in 1926, Anderson retired and sold his AmNews stock to the Davises. They, along with Odessa A. Morse, began publishing under the name E.A. Warren-Davis Publishing Company. Following some years of financial difficulties, in 1936, they sold the publication for $5,000 to New York’s leading Black businessmen, Dr. Cielan Bethan Powell and Dr. Phillip M.H. Savory of the Powell Savory Corporation. At that time, it was the largest newspaper in Harlem with 77 employees, plus 100 paperboys, and sold at 793 newsstands. Powell assumed the role of publisher, a position he held until its sale in 1971.

During Powell’s over 30-year tenure, many prominent Black journalists contributed columns and articles to the paper, such as Marvel Cooke, who joined the staff in 1927 as its first woman reporter; Frankye A. Dixon, another female journalist who joined the staff as a classical music/entertainment reporter and society columnist; W.E.B. Du Bois, who wrote the weekly column “As the Crow Flies”; John Henrik Clarke; Roy Wilkins; and Adam Clayton Powell, Jr.

In 1938, the paper moved again, this time one block away to 2271 Seventh Avenue. In the early 1940s, it relocated to its present headquarters at 2340 Eighth Avenue, also known as Frederick Douglass Boulevard. The two businessmen, Powell and Savory, built the Amsterdam News into a major weekly newspaper with a circulation of over 100,000 and a staff of nearly 100 employees. Under their management, the publication became the first African American newspaper to have all of its departments unionized. It was the second Black newspaper, after the Chicago Defender, to be admitted to the Audit Bureau of Circulations, of which it has been a member since 1930.

Notably, the Amsterdam News was the people’s voice when San Juan Hill’s cultural history was diminished by the displacement of thousands of families (including white, Puerto Rican, and a percentage of Black residents) to make room for Lincoln Center. The powerful city planner Robert Moses forged the project as part of his so-called "Lincoln Square Renewal Project” in the 1950s and 60s, one of New York City's urban renewal programs. Unfortunately, this was the third time Black people had been displaced from their established neighborhoods. It first happened in 1857 when a settlement of mostly Irish and Black residential landowners in Seneca Village were evicted and displaced through eminent domain to make room for Central Park. Their second displacement was from the Tenderloin District to build Penn Station in 1910. “It can be said that these were New York City’s first Harlem communities,” stated John Henrik Clarke, in an Amsterdam News article from June 26, 1976.

In 1971, the paper was purchased for an astounding $2.3 million by a group of investors which included Percy E. Sutton, a former Manhattan Borough President. Wilbert A. Tatum and several Harlem business associates bought the paper in 1983. Under Tatum's leadership, the readership was expanded from local to international communities, fueled by the paper’s investigative reporting on international affairs covering the African diaspora.

In December 1997, Tatum stepped down as publisher and editor-in-chief and passed the torch to his daughter, Elinor Tatum. She has prominently positioned the paper for the 21st century, launching a companion website and online edition, and most recently, Editorially Black, an online news daily. The paper’s comprehensive student internship program offers hands-on journalism experiences while confirming the significance and on-going progress of the Black press in today’s world of social media.

Politically, through its existence, the Amsterdam News has supported Republicans, Democrats, Fusionists, Socialists, and Communists in movements for the advancement of Black people. And, it has also opposed these groups. Anderson was a civil rights activist prominent in Republican circles and was a candidate for Alderman in the 31st district. He proved to be a visionary and astute businessman, who founded a small newspaper that eventually became the largest Black newspaper in Harlem and the fourth largest in the U.S., after the Chicago Defender, the Afro-American and the Pittsburg Courier. The Powell Savory Corporation, following the tradition of Anderson, published news accurately and as fairly as possible. Its reporting of discrimination, hospital facilities, education, and social conditions often became leading stories. The emphasis was always on the accomplishments and progress of Black people. Crime news, while good for circulation, was not highlighted.

The Amsterdam News began actively covering Europe during World War I by devoting space to a London correspondent, who cabled timely reports. Staff reporter and artist William C. Chase covered the 1936 Olympics held in Germany, and reporter and world traveler J.A. Rogers covered The Ethiopian-Italian War, sending daily cables to the paper.

During World War II, the Amsterdam News joined forces with other Black newspapers to fight for civil rights in the armed forces. In the turbulent 1950s and 60s, during the civil rights movement, staff reporter James L. Hicks was in the deep South covering the Emmett Till murder trial, the Little Rock Nine, and James Meredith’s chaotic integration at the University of Mississippi. The paper was the first to focus attention on Malcolm X, and in 1958, began publishing his column “God’s Angry Man.”

Anderson died on June 21, 1931 at the House of Calvary Hospital and was buried in Mt. Olivet Cemetery, although his voiced and written desire was to be buried in Woodlawn Cemetery. In that little notebook already mentioned, Anderson wrote his own epitaph. “I am what I am. Perhaps not what I should be, perhaps no more than you believe me to be but at least I have tried.” (Amsterdam News, December 22, 1934). His epitaph can be applied to those Amsterdam News publishers who succeeded him.

Like Anderson, Tatum offers no apologies for her being. “I am Black. I am female. I am Jewish. I am an entrepreneur. And I am proud of every one of those things. I want to represent people of color in New York and farther afield, whatever box they do or don’t fit in. That’s what I want to do with the Amsterdam News,” she said in an interview with Forward.com in 2023.

The newspaper under Tatum remains the Black advocate of New York, the Black voice of Harlem, and the Black drum of the African Diaspora. It is the Black press, the sword and shield against and for America. “Harlem is the Amsterdam News and we are Harlem,” stated Anderson. The storied legacy of the newspaper that began in San Juan Hill 114 years ago continues today!

Notes

Research for this essay was conducted at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture drawing on the following sources:

Poston, T.R. "The Inside Story." Amsterdam News, December 22, 1934.

Obituary of J.H. Anderson. Chicago Defender, July 4, 1931.

“40 Years Ago” (Editorial). Amsterdam News, December 10, 1949.

Clarke, John Henrik. “Harlem: A Brief History of the World’s Most Famous Community.” Amsterdam News, June, 26, 1976.

“San Juan Hill Project’s Site” (Editorial). Amsterdam News, March 8, 1941.

Berlack-Boozer, Thelma. "1909-1940: The Story of the Amsterdam News.” Amsterdam News, June 29, 1940.

"At Least I Tried, Life of the Amsterdam News Founder” (Editorial). Amsterdam News, December 22, 1934.

Johnson, James Weldon. Black Manhattan. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1930.